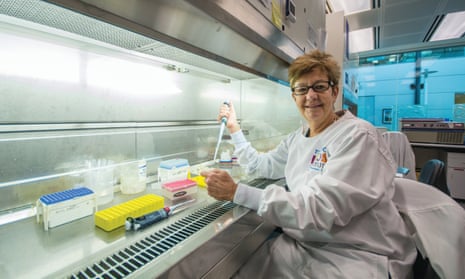

Prof Prue Hart is head of the inflammation research group at the Telethon Kids Institute in Perth, Australia, which studies the beneficial effects of sunlight exposure on our health and whether these are the result of UV-induced vitamin D or other molecules produced in our skin upon exposure to sunlight.

What exactly happens when the sun hits our skin?

Sunlight is made up of three components: there’s the visible light that gives colour to everything we see; infrared light, which provides the heat; and ultraviolet (UV) light, which is probably the most important for our health.

Too much UV is harmful. The most damaging wavelengths are blocked by ozone in the stratosphere, but UVB and UVA wavelengths get through. The worst effect on our skin is sunburn; that’s something we all should avoid because it causes havoc in the skin: there is a breakdown of the normal barrier function and inflammation. It can also affect your skin stem cells – self-renewing cells that can differentiate into the various structural cell types in the outermost layer of your skin.

What about sun exposure that doesn’t give you sunburn?

This also has biological effects, and many of them are positive. A molecule called 7-dehydrocholesterol absorbs UVB, resulting in vitamin D production, which is important for your bones. There are three or four other molecules in the skin that absorb UV and initiate pathways that usually have anti-inflammatory effects. They may be complementary or interactive and may be more prominent at different times of day and in different seasons depending on the UV exposure.

Our skin also contains stores of nitric oxide, and when skin is exposed to sunlight – in particular UVA – their release can affect the vascular system, lowering blood pressure. This may help explain why your blood pressure is lower during the summer months compared with the winter ones. The nitric oxide release by skin upon exposure to sunlight might also affect a person’s risk of associated conditions such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease.

How does sun exposure contribute to cancer?

UV can also be absorbed by DNA in our skin cells and trigger changes or mutations. That’s particularly bad if they occur in your stem cells because, whereas other skin cells grow outwards as they develop and eventually slough off, stem cells remain at the base of the skin. If these continue to accumulate changes, this could eventually lead to the development of a skin cancer cell.

What types of cancer are sun-related?

Most skin cancers are non-melanoma skin cancers, which generally don’t metastasise, or spread. The only one that’s potentially really dangerous is melanoma, which can metastasise, and is responsible for the vast majority of skin cancer deaths – so, vigilance is required. Melanoma only accounts for about 1% of all skin cancers, but is difficult to gauge because the numbers of non-melanoma skin cancers are not recorded in registers.

The other major types are basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), which account for about 68% of skin cancers, and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), which account for about 28%. These don’t usually metastasise and can be easily burned off or cut out if they’re detected.

What influences individuals’ susceptibility to melanoma?

We still don’t fully understand melanoma. Sun exposure increases the risk, but it is not necessarily initiated that way. Genetic susceptibility may be important but they also appear stochastically. Increasingly, it’s thought that melanin [a pigment that influences the shade of someone’s skin] may not play a major role in protecting the stem and progenitor cells at the base of the skin. There are about 17 genes that are known to strongly influence skin pigmentation, and some of these may be contributing towards the development of skin cancers.

Can people with black or brown skin develop sun-related skin cancers?

People with heavily pigmented skin have far fewer melanomas, but they do still get them, though they don’t get them in the same places as those with lighter skin – they tend to get them on the soles of their feet, and other places that may not get a lot of sun exposure. But you can’t necessarily diagnose their skin cancers in quite the same ways as in lighter-skinned people. So, it’s a difficult area that needs a lot more research.

Will the climate crisis and/or thinning atmosphere change our sun exposure?

The peak of the ozone hole was meant to be the 1990s. As a result of the ban on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), the hole has stabilised, but it has not exactly closed. It is still a worry because if you’ve got less ozone, you’ve got more UV reaching the Earth’s surface.

Climate change caused by other greenhouse gases could influence cloud cover. If there are fewer clouds, that could result in more UV exposure. However, it could also result in people spending more time indoors, so the relationship isn’t necessarily straightforward.

Is wearing SPF 100 sun cream overkill?

A sun protection factor (SPF) of 50 is enough. It will block out 98% of UV, whereas an SPF 100 will block out 99%. We do need some UV exposure for our health. I use a sunscreen if I don’t know how long I’m going to be out the sun, and as a way of avoiding a sunburn. I also say you should wear a hat to protect the head and neck, because this is where a lot of skin cancers tend to occur.

White Britons living in the Mediterranean often stop using sun cream once they have reached peak mahogany… Is this wise?

The skin adapts, but it is not absolute. A person with lightly pigmented skin never truly tans, and will certainly be at risk of sunburn if they spend a lot of time out in the sun. Recent work by Antony Young at King’s College London suggests that if you have very lightly pigmented skin, you may have a different sort of melanin, DNA repair and antioxidant capacity, compared with a darker-skinned person, which could affect how your skin responds to UV. These things are influenced by your genetics. Young’s work suggests that tanning affords only a very limited protection – equivalent to a low SPF sunscreen. It doesn’t necessarily protect against DNA damage or sunburn.

Could we harness some of the immunosuppressive benefits of sunlight to combat conditions such as autoimmune disease?

Phototherapy is a type of radiation therapy that mimics the effects of sunlight exposure. It has been used for decades to treat inflammatory skin diseases, but our lab has been investigating whether it could be used to treat more systemic, internal diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or type 1 diabetes, as well.

In our MS trial, we recruited people with the first clinical signs that they might be developing MS, to see if phototherapy might be able to halt or delay its development. Half of them received phototherapy three times a week for eight weeks, and the other half did not. After a year, we noticed a 30% reduction in those that went on to develop MS in the phototherapy group. We also detected different blood immune cell profiles in those who had the phototherapy – particularly their antibody-producing B cells. And these cells also showed a dampened response when we activated them. We think this might be important in the development of MS, where immune cells mistakenly attack the brain and nerves.

How do we balance the negative effects of skin cancer against its positive benefits in everyday life?

I think it all comes down to knowing your skin and not getting sunburned, because sunburn is the only type of sun exposure that has been reliably linked to melanoma. All these other benefits come from sub-erythemal doses of UV – meaning not enough exposure to cause reddening or inflammation of the skin.

The mood element of sun exposure and getting outdoors is also really important for our mental health. So, I think balance is the key.

Linda Geddes is the author of Chasing the Sun: The New Science of Sunlight and How it Shapes Our Bodies and Minds, published by Wellcome Collection (£8.99)